Freedom, just north of Hope

Batey Libertad sits on a little corner of land sandwiched between Highway 1 and an endless mosaic of rice and banana fields in northwest Dominican Republic. The small hamlet just two hours from the Haitian border has become a destination for people fleeing the violence on the other side of the island of Hispaniola. Like so many of the world’s migrants, they are seeking peace and opportunities for work.

But for the most part, Batey Libertad proves not the be the haven they sought.

Haitians play a huge role in the labor force in the Dominican Republic, taking up work in the agriculture sector that many Dominicans are unwilling to do themselves. And yet, the political climate under President Luis Abinader has been to take a hard line against Haitian migrants despite the chaos in Haiti and accusations of racism and xenophobia from the international community.

Residents of Batey Libertad find there is not enough work to rebuild their lives. Only ten minutes down the road is Esperanza, a city of 50,000, with more opportunity for work and commerce. But the two are separated by a militarized checkpoint that screens people seemingly primarily by the color of their skin, putting Esperanza just out of reach. And so, the residents of Batey Libertad wait out each day in fear of the next raid on the village that could send them back across the border.

With reporting by Natalia Galicza for Deseret Magazine.

The sun sets over Batey Libertad and the agricultural fields that offer the only work for many of the batey’s residents.

With few opportunities for work, passing time is the main activity for young and old in the batey.

Joseline

Joseline Geffrard, 32, fled Port-au-Prince after being robbed at gunpoint by gang members while shopping at a market near her home. It was a few months after Haiti’s president had been tortured and killed inside his home. In that political vacuum, gang violence in the country exploded.

After the robbery, Geffrard was gripped with fear and couldn’t bring herself to leave the house. Finally, she made the impossible decision to leave. She left her son and daughter to live with their grandparents so they could continue their education.

From writer Natalia Galicza for Deseret Magazine:

On the last day before Geffrard left for Batey Libertad, she remembers sitting her youngest child on her lap to pepper with motherly advice: “Be good,” and “Listen to your grandmother.” She remembers playing cards with her oldest. How they each asked for one last home-cooked meal. Rice and beans. Legim, a Haitian eggplant and meat stew. Papaya milkshakes. After what would be their final family feast for an indeterminate amount of time, Geffrard fried up some plantains to leave behind. She hoped the extra food could help them feel as though she were still there, at least as long as the leftovers lingered. But based on all the uncertainties — including whether foreign troops will intervene, let alone when — she’s realized there was no amount of plantains she could have prepared to last long enough.

Sandra

It's early evening and Sandra Jean-Mary is selling fried plantains at her street stand in Batey Libertad. Her small business there is an extension of an entrepreneurial life she once had living in Saint-Marc, Haiti. But when the gang violence increased, her customer base evaporated. The cost of food and goods had her eating once a day.

As Natalia Galicza wrote for Deseret Magazine:

Jean-Mary saved enough money to buy herself a visa and cross the border legally. But when she arrived at Batey Libertad, the cost of renewing her documentation grew too steep. She harvested pigeon peas for Dominican pesos and began selling food in the community every evening. Fried plantains, fried chicken, sweet potatoes, pickled spicy cabbage. Still, she did not earn enough for the monthly travel by both bus and moto-taxi for more than two hours to a checkpoint and back to pay for another stamp in her passport. Her documents expired in June. She now fears deportation, has fewer job prospects and faces a smaller chance of repurchasing another yearlong visa to regain legal status.

When Jean-Mary pits the opportunities she has in Haiti against those available to her in the Dominican Republic, she arrives at a quandary. One nation is collapsing due to violence and doesn’t have much of a job market to offer at the moment. The other has a more stable and successful economy, but does not allow her to formally take part in it.

Marie

Marie Sonise Zare, 48, her son, Peni Jameda, 9, and her husband, Michelet Cedor, 44, share a windowless two-room home that occupies one corner of a larger building. The walls are plywood and the roof metal.

While Peni runs through the streets and alleyways with other kids and Michelet busies himself repairing electronics and appliances, Marie sits and waits. She said she doesn’t have any friends in the batey. Despite the violence back in Haiti, she longs for her home.

As Natalia Galicza wrote for Deseret Magazine:

By her son’s mattress, Zare keeps a bag as tall as her packed with clothing. She started assembling it in January and leaves it full, untouched, for the day she works up the nerve to go back to her home country with her son. She planned to depart one week in March but was dissuaded by more news of brutality. So she keeps checking videos online for a green light, a moment of calm. And she keeps the bag packed. It’s how she maintains her hope in a healed Haiti — the same way Jean-Mary cooks food that reminds her of her homeland and Geffrard waits by the phone to hear her children’s voices. In a way, that’s all the migrants can do in Batey Libertad. Wait.

Rosa Mercedes Daniel, 19, Wagdalena Telus, 15, and Duelobi Pierre, 12, hang out on the street.

A military checkpoint screens cars for migrants while a nearby billboard of president Luis Abinader has been vandalized.

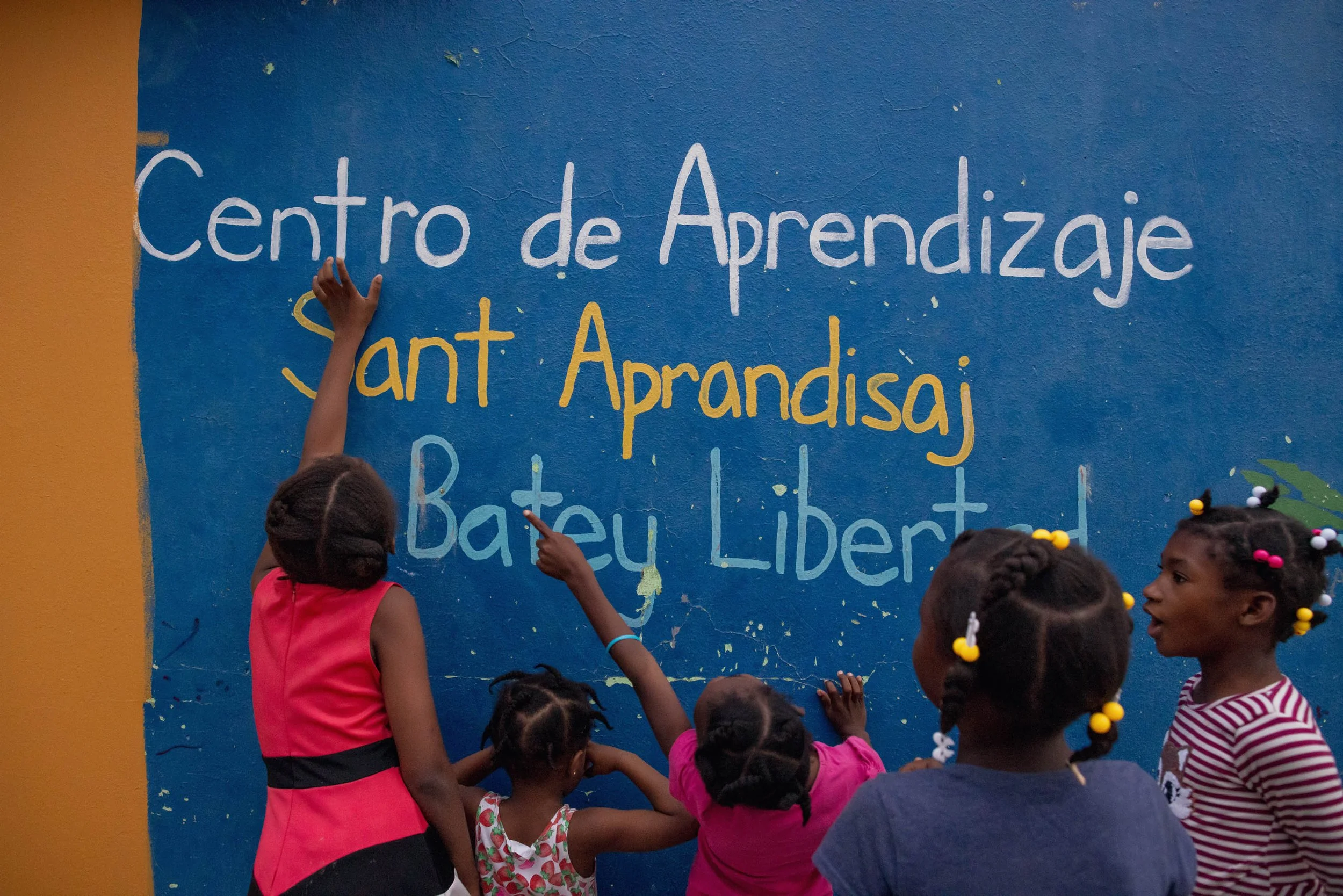

Peeling pigeon peas from nearby farms is a common low-wage job for batey residents, while young girls practice reading a sign for a learning center painted in both Spanish and Creole.

Sandra Jean-Mary sells fried food on the side of the street.

Michelet Cedor, 44, his wife, Marie Sone Zae, 48, and her son, Peni Jameda, 9, in the small home they share in Batey Libertad.

Goats feed on a garbage patch in the town.

Sandra Jean-Mary sits in the back with the young girls during a bible lesson at a Christian church and reads from a Haitian Creole bible.

An agricultural worker lights a cigarette on the edge of a rice field on the edge of Batey Libertad.

Night falls on the batey.